A Horizontal Row Of Elements In The Periodic Table.

Kalali

Mar 12, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Unveiling the Secrets of a Periodic Table Row: A Deep Dive into a Period

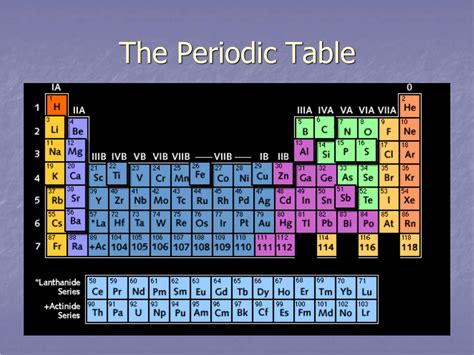

The periodic table, a cornerstone of chemistry, organizes elements based on their atomic structure and properties. While columns (groups) share similar chemical behavior, rows (periods) reveal a fascinating narrative of evolving properties as you traverse across them. This article delves deep into the intricacies of a single period, exploring the trends in atomic radius, ionization energy, electronegativity, and metallic character, culminating in a richer understanding of how these properties dictate chemical behavior and applications.

Understanding Periods: A Foundation for Exploration

A period in the periodic table represents a horizontal row of elements. Each period corresponds to the filling of a principal energy level (shell) with electrons. The first period, for instance, only has two elements, hydrogen and helium, as the first energy level can only accommodate a maximum of two electrons. Subsequent periods have increasing numbers of elements because of the increasing number of sublevels (s, p, d, and f) within the principal energy levels. This progressive addition of electrons significantly influences the properties of the elements within a given period.

Key Periodic Trends within a Period:

Several crucial properties exhibit predictable trends across a period. Understanding these trends is essential for comprehending the chemical reactivity and behavior of elements. Let’s examine some key trends:

-

Atomic Radius: Atomic radius, the distance from the nucleus to the outermost electron shell, generally decreases across a period. This is because, as you move from left to right, the number of protons in the nucleus increases, resulting in a stronger positive charge attracting the electrons more closely. While more electrons are added, they are added to the same principal energy level, not a new, larger one, hence the decrease in size.

-

Ionization Energy: Ionization energy is the energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom or ion. It generally increases across a period. The increasing nuclear charge holds the electrons more tightly, making it progressively harder to remove an electron. Exceptions can occur due to electron configurations and electron-electron repulsions.

-

Electronegativity: Electronegativity is a measure of an atom's ability to attract electrons towards itself in a chemical bond. This value generally increases across a period, mirroring the trend in ionization energy. The increasing nuclear charge enhances the atom's pull on shared electrons in a covalent bond. Noble gases are exceptions, as they have complete valence shells and do not readily participate in bonding.

-

Metallic Character: Metallic character, reflecting the tendency of an element to lose electrons and form positive ions, generally decreases across a period. Elements on the left side of a period are typically metals, characterized by low ionization energies and the readiness to lose electrons. As you move to the right, non-metallic character increases, with elements exhibiting higher ionization energies and a greater tendency to gain electrons. This shift culminates in the noble gases, which are exceptionally unreactive due to their complete electron shells.

A Period-by-Period Analysis: Illustrating the Trends

Let's now delve into a detailed examination of several periods to illustrate these trends more concretely. Due to the length of this analysis, we’ll focus on periods 2 and 3, offering a solid foundation for understanding the principles that extend across all periods.

Period 2: A Microcosm of Periodic Trends

Period 2, encompassing lithium (Li) to neon (Ne), offers a compelling illustration of the periodic trends discussed above.

-

Lithium (Li): An alkali metal, exhibiting a relatively large atomic radius, low ionization energy, low electronegativity, and strong metallic character. Its readiness to lose one electron to achieve a stable noble gas configuration (like helium) makes it highly reactive.

-

Beryllium (Be): An alkaline earth metal, smaller atomic radius than lithium, higher ionization energy, slightly higher electronegativity, and weaker metallic character compared to lithium. Still reactive, but less so than lithium.

-

Boron (B): A metalloid, marking a transition towards non-metallic character. Further reduction in atomic radius, increased ionization energy, and higher electronegativity than beryllium. Its behavior exhibits a blend of metallic and non-metallic properties.

-

Carbon (C): A nonmetal, significantly smaller atomic radius, high ionization energy, and high electronegativity. Its ability to form four covalent bonds, making it a cornerstone of organic chemistry.

-

Nitrogen (N): A nonmetal, even smaller atomic radius, higher ionization energy, and higher electronegativity than carbon. Exists as a diatomic molecule (N2) due to its strong triple bond.

-

Oxygen (O): A nonmetal, with a still smaller atomic radius, high ionization energy, and high electronegativity. Highly reactive, often forming oxides with other elements.

-

Fluorine (F): A halogen, the smallest atomic radius in period 2, highest ionization energy, and highest electronegativity. The most reactive nonmetal, readily forming ionic compounds.

-

Neon (Ne): A noble gas, possessing a complete valence electron shell (octet), making it exceptionally unreactive and chemically inert.

Period 3: Expanding on the Observed Trends

Period 3, from sodium (Na) to argon (Ar), mirrors many of the trends observed in period 2, but with subtle differences due to the increased number of electrons and the presence of a larger principal energy level.

-

Sodium (Na): An alkali metal, behaving similarly to lithium but with a larger atomic radius.

-

Magnesium (Mg): An alkaline earth metal, similar to beryllium but with a larger atomic radius.

-

Aluminum (Al): A metalloid, exhibiting properties intermediate between metals and nonmetals, analogous to boron.

-

Silicon (Si): A metalloid, similar to silicon but with a larger atomic radius. A crucial element in semiconductor technology.

-

Phosphorus (P): A nonmetal, exhibiting allotropic forms (different structural forms) and a greater variety of compounds compared to nitrogen.

-

Sulfur (S): A nonmetal, forming various allotropes and compounds, similar to oxygen but with differences in reactivity.

-

Chlorine (Cl): A halogen, similar to fluorine but with a larger atomic radius and slightly lower electronegativity.

-

Argon (Ar): A noble gas, chemically inert like neon but with a larger atomic radius.

Applications and Real-World Significance

Understanding the properties of elements within a given period has profound implications for various applications and technological advancements. The trends in properties drive the selection of specific elements for particular uses. For example:

-

Semiconductors: Silicon and germanium (period 3 and 4, respectively) are crucial in semiconductor technology due to their unique electrical conductivity, which can be manipulated by doping with other elements.

-

Batteries: Lithium-ion batteries utilize lithium's high reactivity and readiness to lose electrons, enabling energy storage and release.

-

Materials Science: The varying metallic and non-metallic properties across periods allow for the design of alloys and compounds with tailored properties, such as strength, conductivity, and reactivity.

-

Medicine: Elements like iodine (halogen) are crucial in medical applications, and understanding their reactivity is essential in drug design.

-

Catalysis: Transition metals (found in later periods) are frequently employed as catalysts in chemical reactions because of their variable oxidation states and their ability to facilitate the breaking and forming of bonds.

Conclusion: A Holistic Perspective on Periodic Trends

Exploring a single row of the periodic table reveals a microcosm of chemical behavior, dictated by the systematic change in atomic structure. The trends observed – atomic radius, ionization energy, electronegativity, and metallic character – aren't merely abstract concepts; they are the driving forces behind the chemical reactivity and vast applications of elements. A thorough understanding of these trends enables scientists and engineers to design new materials, develop innovative technologies, and ultimately shape the world around us. The seemingly simple horizontal arrangement of elements in the periodic table, therefore, unlocks a universe of scientific exploration and technological innovation. Further research into specific periods and the interplay between different periods will continue to unveil new insights into the fascinating world of chemistry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is 21 Celsius In Fahrenheit

Mar 13, 2025

-

What Is 20 Percent Of 40

Mar 13, 2025

-

What Is 20 Percent Of 60

Mar 13, 2025

-

How Many Cm Is 30 Inches

Mar 13, 2025

-

55 C Is What In Fahrenheit

Mar 13, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Horizontal Row Of Elements In The Periodic Table. . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.