How Does A Igneous Rock Become A Sedimentary Rock

Kalali

Mar 17, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Amazing Journey of Igneous Rock to Sedimentary Rock

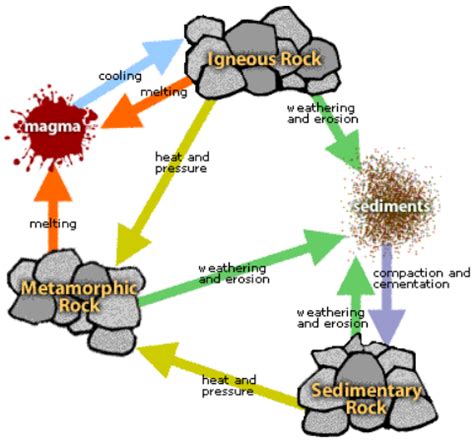

The Earth's rocks are in a constant state of change, a cycle driven by powerful internal and external forces. This incredible transformation, known as the rock cycle, sees rocks morphing from one type to another over vast spans of time. One of the most fascinating aspects of this cycle is the journey of an igneous rock, formed from cooled magma or lava, into a sedimentary rock, composed of fragments of pre-existing rocks. Understanding this metamorphosis requires exploring the intricate processes of weathering, erosion, transportation, deposition, and lithification.

From Molten Magma to Solid Igneous Rock: The Starting Point

Our story begins with igneous rocks. These rocks are born from the cooling and solidification of molten rock, either deep within the Earth's crust (intrusive igneous rocks like granite) or on the Earth's surface (extrusive igneous rocks like basalt). The speed of cooling significantly impacts the texture of the resulting rock. Slow cooling allows for the formation of large crystals, while rapid cooling leads to fine-grained or even glassy textures. The mineral composition also varies depending on the parent magma's chemical makeup.

This initial stage, the formation of the igneous rock itself, sets the stage for its future transformation. The specific minerals present within the igneous rock, its texture, and its overall chemical stability will all play crucial roles in determining how easily it weathers and erodes.

The Forces of Weathering: Breaking Down the Igneous Giant

The first major step in the igneous rock's transformation is weathering. This process involves the physical and chemical breakdown of the rock into smaller fragments. Several factors contribute to this decomposition:

Physical Weathering:

- Frost wedging: Water seeps into cracks within the rock, freezes, expands, and wedges the rock apart. This is especially effective in regions experiencing freeze-thaw cycles.

- Exfoliation: As overlying rock is eroded, the pressure on the underlying rock decreases, causing it to expand and crack parallel to the surface. This creates layers that peel off like the pages of a book.

- Abrasion: Rocks are constantly bombarded by wind, water, and ice, which gradually wear them down. The friction between rocks causes them to break into smaller pieces.

- Thermal expansion and contraction: Repeated heating and cooling cycles can cause rocks to expand and contract, leading to stress and fracturing.

Chemical Weathering:

- Dissolution: Certain minerals, particularly those containing calcite, are soluble in water and dissolve away.

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals in the rock, altering their chemical composition and weakening the rock structure.

- Oxidation: Oxygen reacts with minerals, particularly iron-bearing minerals, creating rust and weakening the rock.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide dissolved in rainwater forms carbonic acid, which reacts with certain minerals, like calcite, causing them to dissolve.

These weathering processes work in concert, gradually reducing the igneous rock into smaller and smaller fragments, a mixture of mineral grains, ions in solution, and clay minerals. The type of weathering that predominates depends on the climate, the composition of the rock, and the length of time exposed to the elements.

Erosion: Transporting the Fragments

Once the igneous rock is broken down into smaller pieces, the process of erosion begins. Erosion involves the removal of these weathered fragments from their original location. Several agents of erosion contribute to this transportation:

- Water: Rain, rivers, and streams are highly effective at eroding and transporting weathered material. The force of flowing water picks up and carries sediment downstream.

- Wind: Wind can transport fine-grained sediments, like sand and dust, over long distances. This is particularly effective in arid and semi-arid regions.

- Ice: Glaciers are powerful agents of erosion, capable of transporting large amounts of rock debris over long distances. As the glacier moves, it scrapes and grinds the underlying rock, picking up and transporting weathered material.

- Gravity: Gravity plays a role in the movement of weathered material downslope, through processes like landslides and rockfalls.

The distance the fragments are transported and the forces involved in their transportation impact the size and shape of the sediment particles. Long-distance transport tends to round and smooth the particles, while shorter distances result in more angular fragments.

Deposition: Settling Down

Eventually, the erosional forces transporting the weathered fragments lose their energy. This may occur when a river enters a lake or ocean, when wind slows down, or when a glacier melts. When this happens, the sediments settle out, a process called deposition. The largest and heaviest particles settle out first, while the finer particles are carried farther before settling. This sorting process creates layers of sediment with varying grain sizes.

The environment where deposition occurs significantly influences the characteristics of the resulting sedimentary rock. Deposition in a fast-flowing river might produce coarse-grained conglomerate, while deposition in a calm lake might produce fine-grained shale. Different environments create distinctive sedimentary structures, providing clues about the past depositional environment.

Lithification: Cementing the Past

The final step in the transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is lithification. This process involves the consolidation of loose sediment into a solid rock. Several factors contribute to lithification:

- Compaction: As layers of sediment accumulate, the weight of the overlying layers compresses the underlying layers, squeezing out water and reducing the pore space between the particles.

- Cementation: Minerals dissolved in groundwater precipitate within the pore spaces between the sediment particles, acting as a cement that binds the particles together. Common cementing agents include calcite, silica, and iron oxides.

The type of cementing agent and the degree of compaction influence the final characteristics of the sedimentary rock. Well-cemented rocks are strong and resistant to weathering, while poorly cemented rocks are more friable.

From Igneous to Sedimentary: A Complete Metamorphosis

The entire journey from igneous rock to sedimentary rock involves a complex interplay of physical and chemical processes spanning vast periods, potentially millions of years. The initial igneous rock, initially strong and resistant, is broken down by weathering, transported by erosion, deposited in layers, and finally cemented into a new sedimentary rock. This transformation preserves a record of the past environments and processes, making sedimentary rocks valuable tools for geologists in reconstructing Earth's history.

Types of Sedimentary Rocks Formed from Igneous Protoliths

The specific type of sedimentary rock formed from an igneous protolith (the original rock) depends heavily on the original composition of the igneous rock and the processes it underwent during weathering, transportation, and deposition. Some examples include:

- Sandstone: Formed from the accumulation and cementation of sand-sized grains, often derived from the weathering of felsic igneous rocks like granite. The quartz grains in granite are particularly resistant to weathering, making them a significant component of many sandstones.

- Conglomerate: A coarse-grained sedimentary rock composed of rounded pebbles and cobbles cemented together. These clasts often originate from the weathering and erosion of igneous rocks, especially those in mountainous regions.

- Shale: A fine-grained sedimentary rock formed from the accumulation of clay minerals, often the product of the chemical weathering of igneous rocks, particularly mafic ones.

- Breccia: Similar to conglomerate, but with angular clasts. This suggests shorter transportation distances and rapid deposition.

The study of sedimentary rocks provides invaluable insights into past geological environments, climates, and the processes that have shaped our planet. Understanding the transformation from igneous to sedimentary rocks highlights the dynamic nature of the Earth and the cyclical nature of geological processes. The rock cycle is a continuous process, and these sedimentary rocks can themselves be transformed into metamorphic or even igneous rocks in the future, continuing the endless cycle of rock transformation.

This detailed exploration of the transformation of igneous rocks into sedimentary rocks emphasizes the intricate processes involved in this geological metamorphosis. Each stage, from weathering to lithification, plays a vital role in the creation of new rock formations, offering a fascinating glimpse into the dynamic and ever-changing nature of our planet. The study of this transformation contributes significantly to our understanding of Earth’s history and the forces shaping its surface.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

3 Feet 6 Inches In Cm

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 26 Out Of 30 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Many Feet Is 26 In

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 6 Out Of 20 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is Melting Point Of Glass

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Does A Igneous Rock Become A Sedimentary Rock . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.