How Does Igneous Rock Turn Into Sedimentary

Kalali

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Incredible Journey: How Igneous Rocks Transform into Sedimentary Rocks

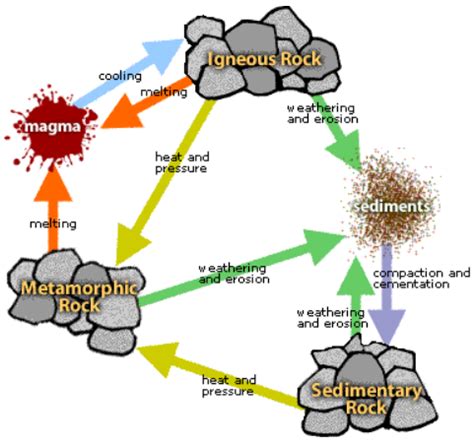

The Earth's dynamic processes are a constant cycle of creation and destruction, and nowhere is this more evident than in the transformation of rocks. One fascinating journey is the metamorphosis of igneous rocks, formed from the cooling of molten magma or lava, into sedimentary rocks, built from layers of sediment. This seemingly straightforward process is actually a complex and fascinating journey, involving several key steps driven by powerful geological forces. Understanding this transformation unveils a deeper appreciation for the planet's ever-changing surface and the vast timescale over which these processes unfold.

From Molten Rock to Solid Igneous: The Starting Point

Before we delve into the sedimentary transformation, let's briefly revisit the origins of igneous rocks. These rocks are primary rocks, formed directly from the solidification of magma (underground molten rock) or lava (molten rock that erupts onto the Earth's surface). The cooling process dictates the rock's texture and mineral composition. Fast cooling leads to fine-grained rocks like basalt, while slow cooling results in coarse-grained rocks like granite. The chemical composition of the magma also plays a critical role, influencing the specific minerals that crystallize within the igneous rock. These igneous rocks, whether intrusive (formed underground) or extrusive (formed above ground), represent the initial stage of our transformation story.

Key Characteristics of Igneous Rocks Relevant to Sedimentary Transformation:

- Mineral Composition: The minerals within the igneous rock will directly influence the type of sediment produced during weathering and erosion. For example, feldspar-rich igneous rocks will yield significant amounts of clay minerals during weathering.

- Rock Strength and Hardness: The resistance of the igneous rock to weathering and erosion impacts the rate at which it breaks down into smaller particles. Harder rocks, like granite, will weather more slowly than softer rocks, like basalt.

- Rock Structure and Texture: Joints, fractures, and the overall texture (fine-grained vs. coarse-grained) influence how easily the rock breaks down into fragments. A highly fractured rock will weather more quickly.

The Demolishing Forces: Weathering and Erosion

The journey from igneous rock to sedimentary rock begins with weathering, the breakdown of rocks at or near the Earth's surface. This process doesn't involve the movement of the broken-down material; it's simply the disintegration and decomposition of the rock in place. There are two main types of weathering:

1. Mechanical Weathering: The Physical Breakdown

Mechanical weathering involves the physical disintegration of rocks without changing their chemical composition. Several processes contribute to this:

- Frost Wedging: Water seeps into cracks in the rock, freezes, expands, and wedges the rock apart. This is particularly effective in cold climates with repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Exfoliation: As overlying rock is eroded, the pressure on underlying rock is released, causing it to expand and fracture parallel to the surface. This creates sheets of rock that peel away.

- Abrasion: Rocks are worn down by the impact of other rocks, sand, or ice. This is common in rivers, glaciers, and deserts.

- Biological Activity: Plant roots can grow into cracks, widening them and breaking the rock apart. Burrowing animals can also contribute to mechanical weathering.

2. Chemical Weathering: The Chemical Transformation

Chemical weathering involves the alteration of the rock's chemical composition. This leads to the formation of new minerals and the weakening of the rock structure. Key processes include:

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals in the rock, breaking them down and forming new minerals, often clay minerals. Feldspar, a common mineral in igneous rocks, is particularly susceptible to hydrolysis.

- Oxidation: Oxygen reacts with minerals, particularly iron-bearing minerals, causing them to rust and weaken. This is evident in the reddish-brown coloration often seen in weathered rocks.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere dissolves in rainwater to form a weak carbonic acid. This acid reacts with some minerals, particularly carbonates, dissolving them.

- Dissolution: Some minerals, like halite (rock salt), simply dissolve in water.

Once the igneous rock has been weathered, erosion takes over. Erosion is the process of transporting the weathered material away from its original location. This can be accomplished through various agents:

- Water: Rivers, streams, and rain are powerful erosional forces, carrying sediment downstream.

- Wind: Wind can transport sand and dust over vast distances.

- Ice: Glaciers can transport enormous quantities of rock and sediment.

- Gravity: Mass wasting events, like landslides, can rapidly transport large amounts of weathered material downslope.

Transportation and Deposition: Shaping the Sediment

The weathered and eroded material, now in the form of sediment – ranging from large boulders to microscopic clay particles – is transported by various agents. During transportation, further breakdown and modification of the sediment occurs. The distance and mode of transport influence the size and shape of the sediment particles. For example, sediment transported by rivers tends to be rounded and well-sorted, while sediment transported by glaciers is often angular and poorly sorted.

Eventually, the sediment is deposited in various environments:

- Rivers and Streams: Sediment is deposited in river channels, floodplains, and deltas.

- Lakes: Sediment accumulates at the bottom of lakes, forming layers of sediment.

- Oceans: Sediment is deposited on the ocean floor, creating vast layers of sediment.

- Deserts: Wind-blown sand accumulates to form dunes and sand sheets.

- Glacial Environments: Glaciers deposit sediment as they melt, creating moraines and other glacial landforms.

Lithification: Cementing the Past

The final stage in the transformation of igneous rocks into sedimentary rocks is lithification. This process involves the transformation of loose sediment into solid rock. Several factors contribute to lithification:

- Compaction: As layers of sediment accumulate, the weight of the overlying sediment compresses the underlying layers, squeezing out water and reducing the pore space between sediment particles.

- Cementation: Dissolved minerals in groundwater precipitate within the pore spaces, binding the sediment particles together and forming a solid rock. Common cementing minerals include calcite, quartz, and iron oxides.

- Recrystallization: Minerals within the sediment can recrystallize, increasing their size and interlocking, further strengthening the rock.

Types of Sedimentary Rocks Derived from Igneous Protoliths:

The specific type of sedimentary rock formed depends on the composition of the original igneous rock and the sedimentary environment. Several examples include:

- Sandstone: Derived from the weathering and erosion of igneous rocks rich in feldspar and quartz.

- Shale: Formed from the accumulation of fine-grained clay minerals, often derived from the weathering of feldspar-rich igneous rocks.

- Conglomerate: Formed from the cementation of large, rounded fragments of igneous rocks, often found in river deposits.

- Breccia: Similar to conglomerate but with angular fragments, indicating less transportation before deposition.

The Rock Cycle Continues: A Continuous Transformation

The transformation of igneous rocks into sedimentary rocks is just one stage in the rock cycle, a continuous process of rock formation, alteration, and destruction. Sedimentary rocks themselves can be metamorphosed into metamorphic rocks under high pressure and temperature, or they can be melted to form magma, eventually cooling to form new igneous rocks. This continuous cycle highlights the dynamic nature of the Earth's crust and the interconnectedness of geological processes. Understanding this cycle provides valuable insights into the Earth's history, its geological evolution, and the formation of the landscapes we see today. It's a testament to the incredible power and enduring influence of Earth’s natural processes. The journey from igneous rock to sedimentary rock, though seemingly simple in its outline, reveals a vast, complex, and deeply fascinating story of transformation spanning millions of years.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Animals Can See Human Bioluminescence

Mar 19, 2025

-

Is Sour Taste A Physical Property

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Many Kilos Are 20 Pounds

Mar 19, 2025

-

11 Out Of 30 As A Percentage

Mar 19, 2025

-

Cuanto Es 92 Grados Fahrenheit En Centigrados

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Does Igneous Rock Turn Into Sedimentary . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.