Reactions Which Do Not Continue To Completion Are Called Reactions.

Kalali

Mar 20, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Reactions That Don't Go to Completion: Understanding Reversible Reactions and Equilibrium

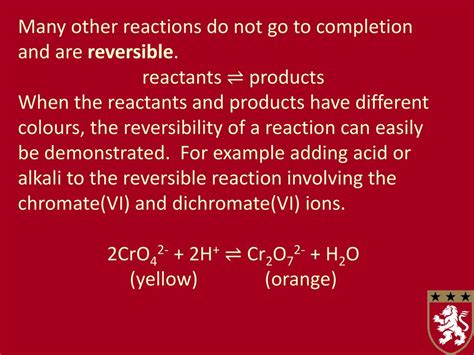

Chemical reactions, the heart of chemistry, are rarely as straightforward as they initially appear. While many reactions proceed until one or more reactants are completely consumed, a significant number reach a point where the forward and reverse reactions occur at equal rates. These are reversible reactions, and they don't go to completion. Instead, they reach a state of dynamic equilibrium. Understanding these reactions is crucial for comprehending various chemical processes, from industrial synthesis to biological systems.

What are Reversible Reactions?

Unlike irreversible reactions, which proceed essentially to completion, consuming reactants to form products, reversible reactions can proceed in both the forward and reverse directions. This means that the products formed can react with each other to reform the original reactants. A classic example is the synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases, known as the Haber-Bosch process:

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)

The double arrow (⇌) signifies the reversibility of the reaction. Under certain conditions, nitrogen and hydrogen react to form ammonia. Simultaneously, some ammonia molecules decompose back into nitrogen and hydrogen.

Factors Affecting Reversibility

Several factors influence the extent to which a reaction is reversible:

-

Temperature: Increasing the temperature often favors the endothermic reaction (the reaction that absorbs heat), while decreasing it favors the exothermic reaction (the reaction that releases heat). This is governed by Le Chatelier's principle.

-

Pressure: Changes in pressure primarily affect reactions involving gases. Increasing pressure favors the side with fewer gas molecules, while decreasing pressure favors the side with more gas molecules. Again, this is a consequence of Le Chatelier's principle.

-

Concentration: Increasing the concentration of reactants drives the reaction forward, producing more products. Conversely, increasing the concentration of products drives the reverse reaction, forming more reactants.

-

Catalyst: A catalyst speeds up both the forward and reverse reactions equally; it doesn't affect the position of equilibrium but reduces the time it takes to reach equilibrium.

Equilibrium: A Dynamic State

When a reversible reaction reaches equilibrium, the rates of the forward and reverse reactions become equal. This doesn't mean that the concentrations of reactants and products are equal; rather, it means that the rate of formation of products equals the rate of formation of reactants. The system appears static at the macroscopic level, but at the microscopic level, both forward and reverse reactions are constantly occurring. This is a dynamic equilibrium.

Equilibrium Constant (Kc)

The position of equilibrium, meaning the relative amounts of reactants and products at equilibrium, is described quantitatively by the equilibrium constant (Kc). For the general reversible reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

The equilibrium constant is expressed as:

Kc = ([C]ᶜ[D]ᵈ) / ([A]ᵃ[B]ᵇ)

where [A], [B], [C], and [D] represent the equilibrium concentrations of the respective species, and a, b, c, and d are their stoichiometric coefficients.

A large Kc value (Kc >> 1) indicates that the equilibrium lies far to the right, meaning that the concentration of products is significantly higher than that of reactants at equilibrium. A small Kc value (Kc << 1) indicates that the equilibrium lies far to the left, meaning that the concentration of reactants is significantly higher than that of products at equilibrium. A Kc value close to 1 indicates that significant amounts of both reactants and products are present at equilibrium.

Le Chatelier's Principle: Predicting Equilibrium Shifts

Le Chatelier's principle states that if a change of condition is applied to a system in equilibrium, the system will shift in a direction that relieves the stress. This principle helps predict how changes in temperature, pressure, or concentration will affect the position of equilibrium.

Applying Le Chatelier's Principle

Let's consider the Haber-Bosch process again:

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g) ΔH = -92 kJ/mol (exothermic)

-

Temperature: Since this reaction is exothermic (ΔH < 0), decreasing the temperature will shift the equilibrium to the right, favoring the formation of ammonia. Increasing the temperature will shift the equilibrium to the left, favoring the decomposition of ammonia.

-

Pressure: This reaction involves a decrease in the number of gas molecules (4 on the left, 2 on the right). Increasing the pressure will shift the equilibrium to the right, favoring the formation of ammonia. Decreasing the pressure will shift the equilibrium to the left.

-

Concentration: Increasing the concentration of either nitrogen or hydrogen will shift the equilibrium to the right, favoring ammonia formation. Increasing the concentration of ammonia will shift the equilibrium to the left.

Importance of Reversible Reactions in Different Fields

Reversible reactions are ubiquitous in various fields:

Industrial Chemistry

Many industrial processes rely on reversible reactions to produce valuable chemicals. The Haber-Bosch process is a prime example, producing ammonia, a crucial component of fertilizers. Other examples include the production of sulfuric acid and the contact process. Optimizing the conditions to maximize the yield of desired products is a key aspect of industrial chemical processes.

Biological Systems

Biological systems are inherently dynamic, and many biochemical reactions are reversible. Enzyme-catalyzed reactions, for example, often operate close to equilibrium, allowing for efficient regulation and control of metabolic pathways. The reversible binding of oxygen to hemoglobin is a crucial process for oxygen transport in the blood.

Environmental Chemistry

Reversible reactions play a crucial role in environmental processes, such as the dissolution and precipitation of minerals in aquatic systems, the acid-base equilibria in lakes and oceans, and the atmospheric reactions involving greenhouse gases. Understanding these reactions is essential for assessing and mitigating environmental impacts.

Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations

Determining the equilibrium concentrations of reactants and products often involves solving simultaneous equations. For simple reactions, an ICE (Initial, Change, Equilibrium) table can be used to systematically track the changes in concentration as the reaction proceeds toward equilibrium. The equilibrium concentrations are then used to calculate the equilibrium constant.

Example: Using ICE Table

Let's say we have the following reversible reaction:

A ⇌ B

Initially, we have 1.0 mol of A and 0 mol of B in a 1.0 L container. If the equilibrium constant, Kc, is 0.5, we can use an ICE table to calculate the equilibrium concentrations:

| Species | Initial (M) | Change (M) | Equilibrium (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.0 | -x | 1.0 - x |

| B | 0 | +x | x |

Substituting into the equilibrium expression:

Kc = [B] / [A] = x / (1.0 - x) = 0.5

Solving for x:

x = 0.5(1.0 - x) x = 0.5 - 0.5x 1.5x = 0.5 x = 1/3

Therefore, the equilibrium concentrations are:

[A] = 1.0 - x = 1.0 - 1/3 = 2/3 M [B] = x = 1/3 M

This illustrates a basic calculation. More complex reactions may require more sophisticated techniques, such as the quadratic formula or iterative methods, to solve for equilibrium concentrations.

Distinguishing Between Reversible and Irreversible Reactions

While the distinction might seem clear-cut, practically determining whether a reaction is reversible or irreversible can be nuanced. Several factors contribute:

-

Reaction Completion: Irreversible reactions proceed essentially to completion, consuming almost all reactants. Reversible reactions reach equilibrium with significant amounts of both reactants and products remaining.

-

Thermodynamic Considerations: Highly exothermic reactions with large negative Gibbs Free Energy changes (ΔG << 0) are generally considered irreversible. Reactions with small ΔG values are more likely to be reversible.

-

Experimental Observations: Observing the reaction's behavior under different conditions can provide clues. If changing conditions (temperature, pressure, concentration) causes a noticeable shift in the relative amounts of reactants and products, the reaction is likely reversible.

Conclusion

Reactions that don't continue to completion, namely reversible reactions, are fundamental to understanding a wide range of chemical processes. The concept of dynamic equilibrium, governed by factors such as temperature, pressure, and concentration, and described quantitatively by the equilibrium constant, is crucial for predicting and manipulating reaction outcomes. Le Chatelier's principle provides a powerful tool for predicting the response of equilibrium systems to external changes. Understanding reversible reactions is vital in industrial chemistry, biological systems, and environmental science, highlighting their pervasive importance across diverse scientific disciplines.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Boiling An Egg A Chemical Change

Mar 20, 2025

-

2 5 Gallons Is How Many Quarts

Mar 20, 2025

-

Cuantas Onzas Tiene Un Litro De Agua

Mar 20, 2025

-

What Is 70 F In Celsius

Mar 20, 2025

-

1 Cup Sour Cream To Oz

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Reactions Which Do Not Continue To Completion Are Called Reactions. . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.