What Is At The Heart Of Hypothesis Testing In Statistics

Kalali

Mar 19, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

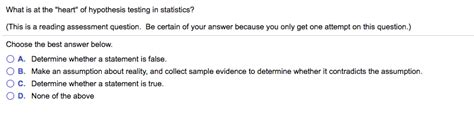

What's at the Heart of Hypothesis Testing in Statistics?

Hypothesis testing is a cornerstone of inferential statistics, a powerful tool that allows us to draw conclusions about a population based on a sample of data. It's used across diverse fields, from medicine and engineering to social sciences and business, to make informed decisions in the face of uncertainty. But what truly lies at the heart of this process? It's a systematic approach to evaluating evidence and making probabilistic judgments, balancing the risk of making incorrect conclusions with the desire to glean meaningful insights from data.

Understanding the Core Components

At its core, hypothesis testing involves a structured process designed to assess the plausibility of a claim or hypothesis about a population parameter. This process hinges on several crucial components:

1. The Null Hypothesis (H₀): The Status Quo

The null hypothesis represents the status quo, the default assumption we're trying to disprove. It typically states there's no effect, no difference, or no relationship between variables. For example:

- In a medical trial: The null hypothesis might be that a new drug has no effect on blood pressure compared to a placebo.

- In a marketing campaign: The null hypothesis might be that a new advertising strategy doesn't increase sales.

- In a social science study: The null hypothesis might be that there's no correlation between education level and income.

It's crucial to note that we don't prove the null hypothesis; we either fail to reject it (meaning we lack sufficient evidence to disprove it) or reject it (meaning we have sufficient evidence to suggest it's unlikely to be true).

2. The Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ): Challenging the Status Quo

The alternative hypothesis is the opposite of the null hypothesis. It's the claim we're trying to support with our data. It can be:

- One-tailed (directional): Specifies the direction of the effect. For example: "The new drug lowers blood pressure."

- Two-tailed (non-directional): Simply states there's a difference or effect without specifying the direction. For example: "The new drug affects blood pressure."

The choice between a one-tailed and two-tailed test depends on the research question and prior knowledge.

3. Test Statistic: Quantifying the Evidence

The test statistic is a numerical value calculated from the sample data. It measures the discrepancy between the observed data and what would be expected if the null hypothesis were true. Different statistical tests use different test statistics (e.g., t-statistic, z-statistic, chi-square statistic, F-statistic). The value of the test statistic is used to determine the p-value.

4. P-value: The Probability of Observing the Data (or More Extreme Data) if the Null Hypothesis is True

The p-value is the probability of observing the obtained results (or more extreme results) if the null hypothesis were true. A small p-value suggests that the observed data is unlikely to have occurred by chance alone if the null hypothesis were true. This leads us to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The threshold for rejecting the null hypothesis is usually set at a significance level (alpha), commonly 0.05.

5. Significance Level (α): Setting the Threshold for Rejection

The significance level (α) is a pre-determined probability threshold. It represents the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it's actually true (Type I error). A common significance level is 0.05, meaning there's a 5% chance of rejecting the null hypothesis when it's true. Choosing the appropriate alpha level involves balancing the risk of making a Type I error against the risk of making a Type II error (failing to reject a false null hypothesis).

6. Critical Region: Defining the Rejection Zone

The critical region is the range of values of the test statistic that lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis. It's determined by the significance level and the distribution of the test statistic under the null hypothesis. If the calculated test statistic falls within the critical region, the null hypothesis is rejected.

7. Type I and Type II Errors: The Risks of Incorrect Decisions

Hypothesis testing always carries the risk of making incorrect conclusions:

- Type I Error (False Positive): Rejecting the null hypothesis when it's actually true. The probability of a Type I error is equal to the significance level (α).

- Type II Error (False Negative): Failing to reject the null hypothesis when it's actually false. The probability of a Type II error is denoted by β. The power of a test (1-β) represents the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis.

The Importance of Choosing the Right Test

The choice of statistical test depends critically on several factors:

- The type of data: Is it continuous, categorical, ordinal?

- The number of groups being compared: Are you comparing two groups, or more than two?

- The assumptions of the test: Many tests rely on assumptions about the data, such as normality or independence of observations. Violating these assumptions can lead to inaccurate results.

Beyond the Basics: Considerations for Robust Hypothesis Testing

While the framework outlined above forms the core of hypothesis testing, several additional considerations enhance the robustness and interpretability of the results:

1. Effect Size: Quantifying the Magnitude of the Effect

The p-value only indicates the statistical significance of the results; it doesn't necessarily reflect the practical significance or the magnitude of the effect. Effect size measures the strength of the relationship between variables or the magnitude of the difference between groups. Reporting effect size alongside the p-value provides a more complete picture of the findings.

2. Confidence Intervals: Estimating the Range of Plausible Values

Confidence intervals provide a range of plausible values for the population parameter of interest. A 95% confidence interval, for example, means that if we were to repeat the study many times, 95% of the confidence intervals would contain the true population parameter. Confidence intervals offer a more nuanced understanding of the results than p-values alone.

3. Power Analysis: Determining Sample Size

Power analysis helps determine the appropriate sample size needed to detect a meaningful effect with a specified level of power (1-β). Insufficient power can lead to Type II errors, while excessively large sample sizes can be inefficient and costly.

4. Assumptions and Their Violations: Addressing Potential Biases

Many statistical tests rely on specific assumptions about the data. Violating these assumptions can affect the validity of the results. Therefore, it's crucial to check the assumptions before conducting the hypothesis test and consider alternative methods if assumptions are violated. Techniques like transformations or non-parametric tests can sometimes mitigate the impact of assumption violations.

5. Multiple Comparisons: Controlling for False Positives

When conducting multiple hypothesis tests, the probability of making at least one Type I error increases. Multiple comparison corrections (e.g., Bonferroni correction, Benjamini-Hochberg procedure) adjust the significance level to control for the inflated Type I error rate.

Conclusion: A Powerful Tool for Evidence-Based Decision Making

Hypothesis testing is a fundamental tool in statistics, providing a rigorous framework for evaluating evidence and making inferences about populations. Understanding its core components, including the null and alternative hypotheses, test statistics, p-values, and significance levels, is essential for conducting and interpreting hypothesis tests correctly. However, it's equally crucial to consider factors such as effect size, confidence intervals, power analysis, and the assumptions of the tests to ensure the robustness and validity of the findings. By carefully considering these aspects, researchers and practitioners can leverage the power of hypothesis testing to make informed decisions based on sound statistical evidence. Remember that hypothesis testing is a process, a journey of inquiry, not a singular point of conclusion. The results inform further investigation, refining our understanding and driving further research.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Que Planeta Esta Mas Cerca Del Sol

Mar 19, 2025

-

14 5 Out Of 20 As A Percentage

Mar 19, 2025

-

Lines In The Same Plane That Never Intersect

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Many Millimeters In 3 4 Of An Inch

Mar 19, 2025

-

15 As A Percentage Of 60

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is At The Heart Of Hypothesis Testing In Statistics . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.