Why Do Neurons And Some Other Specialized Cells Divide Infrequently

Kalali

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Why Do Neurons and Some Other Specialized Cells Divide Infrequently?

The human body is a marvel of cellular organization, comprising trillions of cells working in concert. While many cell types, like skin cells and those lining the gut, constantly divide and renew themselves, some specialized cells, notably neurons and certain others, divide infrequently or not at all after reaching maturity. This characteristic has profound implications for tissue repair, aging, and disease. Understanding why these cells exhibit this limited replicative capacity is crucial for advancing our knowledge of human biology and developing effective therapies for neurological and other age-related conditions.

The Cell Cycle and its Regulation: A Foundation for Understanding Cell Division

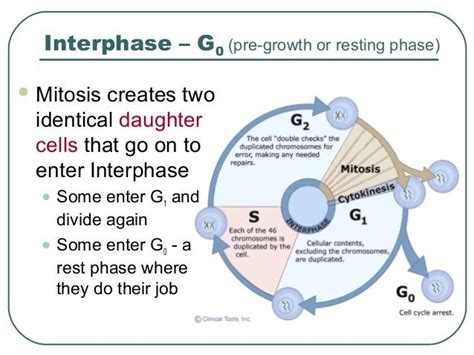

Before delving into the reasons behind infrequent division in specialized cells, it's essential to understand the fundamental process of cell division, known as the cell cycle. The cell cycle is a tightly regulated series of events that leads to cell growth and division, ultimately producing two daughter cells. This cycle consists of several phases:

- G1 (Gap 1): The cell grows in size, synthesizes proteins and organelles, and prepares for DNA replication.

- S (Synthesis): DNA replication occurs, creating two identical copies of each chromosome.

- G2 (Gap 2): The cell continues to grow and prepares for mitosis.

- M (Mitosis): The replicated chromosomes are separated and distributed equally to two daughter nuclei. This is followed by cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, resulting in two distinct daughter cells.

The progression through the cell cycle is controlled by a complex network of regulatory proteins, including cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). These proteins act as checkpoints, ensuring that the cell cycle progresses only when appropriate conditions are met. If errors are detected, the cell cycle can be arrested, allowing for DNA repair or triggering apoptosis (programmed cell death).

Checkpoints: Guardians of Genomic Integrity

The cell cycle checkpoints are crucial for maintaining genomic stability. These checkpoints monitor various aspects of the cell cycle, including DNA integrity, cell size, and the proper attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle. The major checkpoints are:

- G1 checkpoint: This checkpoint determines whether the cell proceeds to DNA replication. It assesses cell size, nutrient availability, and the presence of DNA damage.

- G2 checkpoint: This checkpoint checks for DNA replication completion and the presence of DNA damage before the cell enters mitosis.

- M checkpoint (Spindle checkpoint): This checkpoint ensures that all chromosomes are properly attached to the mitotic spindle before chromosome segregation begins.

Dysregulation of these checkpoints can lead to uncontrolled cell division, a hallmark of cancer.

Why Specialized Cells Divide Infrequently: A Multifaceted Explanation

The infrequent division of neurons and other specialized cells is a consequence of several factors, intricately intertwined and often cell-type specific:

1. Terminal Differentiation and Loss of Cell Cycle Machinery:

Many specialized cells, including neurons, undergo terminal differentiation. This process involves a permanent commitment to a specific cell fate, characterized by the expression of cell-type-specific genes and the loss of the ability to divide. During terminal differentiation, components of the cell cycle machinery, such as cyclins and CDKs, are often downregulated or degraded. This effectively removes the cell's capacity to re-enter the cell cycle. This process is irreversible in most cases.

2. Cell Cycle Inhibitors and Repressive Signaling Pathways:

The expression of cell cycle inhibitors, like p21 and p16, plays a critical role in suppressing cell division in terminally differentiated cells. These inhibitors bind to and inactivate CDKs, preventing the progression through the cell cycle. Furthermore, specific signaling pathways, such as the retinoblastoma (Rb) pathway, are crucial in maintaining the differentiated state and preventing cell cycle re-entry.

3. Structural and Functional Constraints:

The highly specialized morphology and function of certain cell types also contribute to their limited replicative potential. For example, neurons have intricate branching structures (dendrites and axons) that extend over long distances. Cell division in such a complex structure would be extremely challenging, potentially disrupting neuronal function and connectivity. Similarly, the highly specialized contractile apparatus of cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells) makes cell division incompatible with their function.

4. Energetic Demands and Resource Allocation:

Cell division is an energy-intensive process. Specialized cells often prioritize their specialized functions over cell division. Resources are allocated to maintaining cellular function and performing their specialized tasks, rather than dedicating energy to the complex processes of DNA replication and cell division. This metabolic prioritization further reinforces the infrequent division observed in these cell types.

5. Genomic Instability and the Risk of Mutation Accumulation:

The continuous cell division in many cell types increases the risk of accumulating mutations in their DNA. These mutations can have deleterious effects, leading to cell dysfunction or transformation into cancer cells. Infrequent cell division in specialized cells minimizes this risk, thereby preserving genomic integrity and cellular function throughout the lifespan.

Cell-Specific Examples: Beyond Neurons

While neurons serve as a prime example, other specialized cells also demonstrate infrequent division:

- Cardiac Myocytes: Heart muscle cells have a limited capacity for regeneration. Their infrequent division contributes to the limited ability of the heart to repair itself after injury.

- Skeletal Muscle Cells: While skeletal muscle possesses some regenerative capacity through satellite cells, the mature muscle fibers themselves divide infrequently.

- Photoreceptor Cells (Retinal Cells): These light-sensitive cells in the retina have limited regenerative capacity, contributing to the irreversible vision loss associated with certain retinal diseases.

- Pancreatic Beta Cells: These cells produce insulin, and their limited regenerative capacity contributes to the challenges in treating type 1 diabetes.

Implications for Disease and Aging:

The limited regenerative capacity of these specialized cells has significant implications for disease and aging:

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: The inability of neurons to replace themselves significantly contributes to the progressive neuronal loss seen in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions.

- Heart Failure: The limited regenerative potential of cardiomyocytes hinders the heart's ability to recover from myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Age-Related Decline: The gradual loss of specialized cells throughout the aging process contributes to age-related decline in organ function and overall health.

Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions:

Research efforts are actively exploring strategies to enhance the regenerative capacity of specialized cells:

- Stem Cell Therapy: Stem cells, which have the potential to differentiate into various cell types, are being investigated as a therapeutic approach to replace lost or damaged specialized cells.

- Gene Therapy: Manipulating gene expression to promote cell division or enhance cell survival could potentially improve the regenerative capacity of specialized cells.

- Pharmacological Interventions: Drugs that target specific signaling pathways involved in cell cycle regulation are being explored to stimulate cell division in specialized cells.

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in developing effective therapies that can safely and efficiently induce cell division in specialized cells without compromising their function or causing adverse effects.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act Between Specialization and Regeneration

The infrequent division of neurons and other specialized cells is a complex phenomenon shaped by the intricate interplay of developmental programs, cell cycle regulation, and cellular function. While this limited replicative capacity ensures genomic stability and the maintenance of specialized functions, it also contributes to the vulnerability of these cells to injury and age-related decline. Further research into the underlying mechanisms and the development of novel therapeutic strategies are crucial to harnessing the regenerative potential of these cell types and improving human health. The pursuit of this knowledge represents a significant challenge and opportunity in biomedical research, with potential far-reaching benefits for treating a wide array of diseases and improving the quality of life as we age.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is 1 5 8 As A Decimal

Mar 17, 2025

-

3 Feet 6 Inches In Cm

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 26 Out Of 30 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Many Feet Is 26 In

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 6 Out Of 20 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Why Do Neurons And Some Other Specialized Cells Divide Infrequently . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.