How Do Igneous Rocks Form Into Sedimentary Rocks

Kalali

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Amazing Transformation: How Igneous Rocks Become Sedimentary Rocks

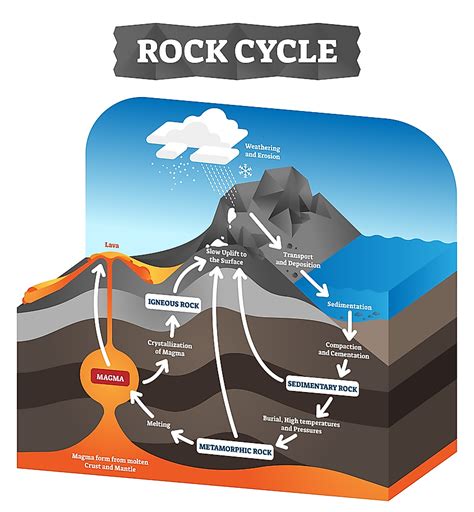

The Earth's crust is a dynamic tapestry woven from a variety of rock types, each with its own unique story to tell. Among the most fascinating transformations is the journey of igneous rocks—born from the fiery depths of volcanoes and molten magma—into sedimentary rocks—the quiet architects of landscapes, formed from the accumulation and cementation of sediments. This article delves into the intricate processes that govern this metamorphosis, exploring the weathering, erosion, transportation, deposition, and lithification that sculpt igneous rocks into their sedimentary counterparts.

From Fiery Birth to Gradual Demise: The Weathering of Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks, forged in the heart of the Earth, are initially characterized by their strength and durability. However, even the most resilient rocks are not immune to the relentless forces of weathering, the process that breaks down rocks at or near the Earth's surface. This crucial first step in the transformation begins the long journey from igneous to sedimentary rock.

Mechanical Weathering: The Physical Breakdown

Mechanical weathering involves the physical disintegration of igneous rocks without altering their chemical composition. Several processes contribute to this breakdown:

- Frost wedging: Water seeps into cracks and fissures in the rocks. As the temperature drops, the water freezes and expands, exerting pressure on the rock's structure, causing cracks to widen and eventually break apart the rock. This is particularly effective in regions with significant freeze-thaw cycles.

- Salt wedging: Similar to frost wedging, salt crystals can grow within rock pores, exerting pressure and causing the rock to fracture. This is common in arid and coastal environments where salt solutions evaporate, leaving behind salt crystals.

- Abrasion: Rocks constantly collide with each other due to forces like wind, water, and glacial movement. This constant friction grinds away at the rock's surface, creating smaller fragments. Think of the relentless tumbling of rocks in a riverbed.

- Exfoliation: As pressure is released from overlying rock layers, the igneous rock expands, causing it to crack and peel off in sheets. This process is often observed in large igneous intrusions.

Chemical Weathering: The Alteration of Composition

Chemical weathering involves the decomposition of igneous rocks through chemical reactions, altering their mineral composition. Key processes include:

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals in the igneous rock, causing them to break down into clay minerals and other soluble substances. Feldspar, a common mineral in many igneous rocks, is particularly susceptible to hydrolysis.

- Oxidation: Oxygen in the atmosphere reacts with minerals, particularly iron-bearing minerals, resulting in the formation of iron oxides. This process often leads to the characteristic reddish-brown coloration observed in many sedimentary rocks.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere dissolves in rainwater, forming carbonic acid. This weak acid reacts with minerals like calcite and feldspar, dissolving them and creating soluble ions. This is particularly important in the weathering of limestone, which is often derived from the weathering of igneous rocks containing calcium-bearing minerals.

- Dissolution: Certain minerals, such as halite (salt) and gypsum, readily dissolve in water, leaving behind no solid residue. While less common in the direct weathering of igneous rocks, this process contributes to the overall sediment load available for sedimentary rock formation.

The combination of mechanical and chemical weathering processes diligently chips away at the solid igneous rock, producing a variety of sediment sizes, from large boulders to microscopic clay particles. This heterogeneous collection forms the raw material for the creation of sedimentary rocks.

Erosion and Transportation: The Journey of Sediments

Once the igneous rock has been weathered into smaller fragments, the next stage involves erosion, the process of removing and transporting the weathered material. Several agents of erosion contribute to this movement:

- Water: Rivers, streams, and rain are highly effective agents of erosion, carrying sediment downstream. The energy of flowing water dictates the size of sediment that can be transported; faster currents can move larger particles.

- Wind: Wind can transport smaller particles, like sand and dust, over vast distances. Sand dunes are a testament to the power of wind erosion and transportation.

- Ice: Glaciers are powerful agents of erosion, capable of transporting huge quantities of rock debris over long distances. The grinding action of glaciers produces a characteristically fine-grained sediment.

- Gravity: Mass wasting events, such as landslides and rockfalls, rapidly transport large quantities of sediment downslope.

The distance sediments travel depends largely on their size and the energy of the transporting agent. Larger particles tend to be deposited closer to their source, while finer particles can be carried much farther. This differential transportation contributes to the layering and sorting seen in many sedimentary rocks.

Deposition: The Settling of Sediments

Deposition occurs when the energy of the transporting agent decreases, causing the sediments to settle out of the water or air. This happens in a variety of environments:

- Rivers and streams: Sediments are deposited in riverbeds, floodplains, and deltas where the water velocity slows down.

- Lakes and oceans: Fine-grained sediments settle out in calm waters, forming layers of mud and silt.

- Deserts: Wind deposits sand in dunes and other features.

- Glacial environments: Glaciers deposit a wide range of sediments, from boulders to fine clay particles.

The environment of deposition significantly impacts the characteristics of the resulting sedimentary rock. For instance, river deposits often show cross-bedding, while lake deposits may exhibit fine laminations.

Lithification: Turning Sediment into Rock

The final stage in the transformation of igneous rock into sedimentary rock is lithification, the process that converts loose sediment into solid rock. Several processes contribute to lithification:

- Compaction: As sediment accumulates, the weight of overlying layers compresses the sediment, reducing its volume and squeezing out water. This process is especially important in fine-grained sediments like mud.

- Cementation: Dissolved minerals in groundwater precipitate within the pore spaces between sediment grains, binding the grains together and forming a solid rock. Common cementing agents include calcite, silica, and iron oxides.

The type of cementing agent and the degree of compaction significantly influence the properties of the resulting sedimentary rock. For example, a well-cemented sandstone will be much stronger than a poorly cemented one.

Types of Sedimentary Rocks Derived from Igneous Sources

The sedimentary rocks formed from the weathered products of igneous rocks are diverse, reflecting the variety of igneous rock types and weathering processes. Some common examples include:

- Sandstone: Formed from the cementation of sand-sized grains, often derived from the weathering of felsic igneous rocks like granite.

- Shale: Formed from the compaction and cementation of clay-sized particles, resulting from the chemical weathering of various igneous rocks.

- Conglomerate: Formed from the cementation of rounded gravel and pebbles, indicating high-energy depositional environments and potentially derived from a variety of igneous sources.

- Breccia: Similar to conglomerate, but composed of angular fragments, suggesting deposition closer to the source of the igneous rock fragments.

Conclusion: A Continuous Cycle

The transformation of igneous rocks into sedimentary rocks is a fundamental part of the rock cycle, a continuous process of rock formation, destruction, and reformation. This complex interplay of weathering, erosion, transportation, deposition, and lithification shapes the Earth's surface, creating the diverse landscapes we see today. Understanding these processes is essential to appreciating the interconnectedness of Earth's systems and the dynamic nature of our planet. The journey from fiery igneous origins to the quiet layers of sedimentary formations is a testament to the powerful and relentless forces that shape our world. From the microscopic alteration of minerals to the grand sweep of glacial movement, the formation of sedimentary rocks from igneous precursors is a fascinating narrative written in stone.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Why Did Scientists Not Accept The Continental Drift Hypothesis

Mar 19, 2025

-

How To Calculate The Ph At The Equivalence Point

Mar 19, 2025

-

Why Cant Freshwater Fish Survive In Saltwater

Mar 19, 2025

-

29 Inches Is How Many Centimeters

Mar 19, 2025

-

126 Inches Is How Many Feet

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Do Igneous Rocks Form Into Sedimentary Rocks . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.