Which Joint Is More Stable The Hip Or The Knee

Kalali

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Hip vs. Knee: Which Joint Is More Stable? A Deep Dive into Anatomy and Biomechanics

The question of which joint, the hip or the knee, is more stable is a complex one, lacking a simple yes or no answer. Stability isn't a monolithic property; it's a multifaceted concept influenced by bony architecture, ligamentous support, muscular control, and even the surrounding soft tissues. Both the hip and knee play crucial roles in locomotion and weight-bearing, each employing unique strategies to maintain stability during various activities. This in-depth analysis will explore the anatomical and biomechanical factors contributing to the stability of each joint, ultimately illuminating the nuances of this comparison.

The Hip Joint: A Ball-and-Socket Bastion of Stability

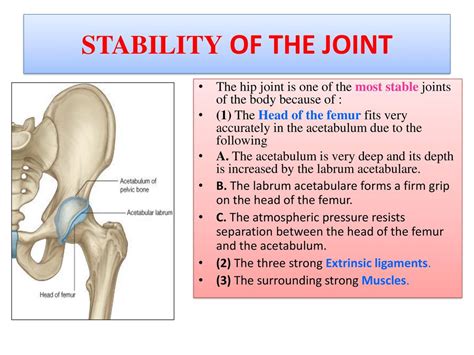

The hip joint, a classic ball-and-socket articulation, boasts inherent stability superior to the knee. This inherent stability arises from several key factors:

1. Deep Acetabulum: A Secure Socket

The hip's acetabulum, the concave socket receiving the femoral head (the ball), is significantly deeper than the tibial plateaus receiving the femoral condyles in the knee. This deep socket inherently restricts excessive movement, providing considerable passive stability. The acetabular labrum, a ring of fibrocartilage lining the acetabulum, further enhances this containment, deepening the socket and improving congruency.

2. Strong Ligamentous Support: A Multifaceted Network

The hip joint benefits from a robust network of ligaments, providing powerful passive restraint against undesirable movements. These ligaments include:

-

Iliofemoral ligament: Often called the "Y-ligament," this strong ligament is the primary stabilizer of the hip, preventing hyperextension and limiting excessive internal and external rotation.

-

Pubofemoral ligament: Situated inferiorly, this ligament resists abduction and external rotation.

-

Ischiofemoral ligament: Located posteriorly, it limits internal rotation and hyperextension.

The combined action of these ligaments creates a powerful constraint system, limiting potentially destabilizing forces.

3. Powerful Muscle Encirclement: Active Stability

Surrounding the hip joint is a complex array of powerful muscles providing crucial active stability. These muscles dynamically adjust their tension to maintain joint integrity throughout various movements and loads:

-

Gluteus maximus: A major extensor and external rotator, it plays a critical role in controlling hip extension and preventing anterior displacement of the femoral head.

-

Gluteus medius and minimus: These abductors are essential for maintaining pelvic stability during single-leg stance, preventing the pelvis from dropping on the unsupported side.

-

Iliopsoas: A powerful hip flexor, it also contributes to stability by controlling hip flexion.

-

Hamstrings: These posterior thigh muscles contribute to hip extension and external rotation, assisting in controlling movement and maintaining stability.

The coordinated action of these muscles provides dynamic stability, adapting to changing loads and movements, far exceeding the passive support of ligaments alone.

4. Bony Congruence: A Natural Fit

The close anatomical fit between the femoral head and acetabulum contributes significantly to hip stability. The spherical femoral head sits snugly within the acetabulum, limiting the potential for abnormal movement. This inherent congruency minimizes the reliance on purely passive restraints.

The Knee Joint: A Hinge with Compromises

The knee, a complex hinge joint, while crucial for locomotion, is inherently less stable than the hip. Several anatomical features contribute to this:

1. Shallow Tibial Plateaus: A Less Secure Socket

Unlike the deep acetabulum of the hip, the tibial plateaus (the articulating surfaces on the tibia) are relatively shallow. This shallower articulation provides less inherent bony constraint, making the knee more susceptible to instability. The lack of a bony ring analogous to the acetabular labrum further contributes to this vulnerability.

2. Collateral Ligaments: Lateral Support

The knee relies on strong collateral ligaments for lateral stability:

-

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Resists valgus forces (medial stress).

-

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): Resists varus forces (lateral stress).

These ligaments are crucial, but their primary role is in preventing excessive sideways movement, rather than providing the comprehensive restraint offered by the hip's multifaceted ligamentous network.

3. Cruciate Ligaments: Anterior-Posterior Stability

The cruciate ligaments are essential for anterior-posterior stability:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Prevents anterior displacement of the tibia on the femur.

-

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL): Prevents posterior displacement of the tibia on the femur.

These ligaments play a vital role in preventing excessive forward and backward movement, but they don't completely address all possible instability vectors.

4. Menisci: Shock Absorption and Congruency

The medial and lateral menisci are fibrocartilaginous structures that improve joint congruency and act as shock absorbers. While they contribute to stability by improving the fit between the femur and tibia, they are not primary stabilizers in the same way as the hip's ligaments.

5. Muscular Support: Less Encompassing

While muscles surrounding the knee, such as the quadriceps (anterior) and hamstrings (posterior), provide crucial active stability, their arrangement is less encompassing than the hip's muscular encirclement. The knee relies heavily on dynamic muscular control, but this active stability is more susceptible to fatigue and neuromuscular dysfunction.

Comparing Stability: A Holistic Perspective

While the hip's inherent bony architecture, strong ligamentous support, and powerful muscle encirclement provide superior passive and active stability, the knee relies more heavily on dynamic muscular control and robust, but less comprehensive, ligamentous structures.

The knee’s increased vulnerability to injury is partly due to its weight-bearing role combined with its less inherently stable design. The knee’s range of motion, while advantageous for functional activities, also increases its susceptibility to injury.

Therefore, declaring one joint definitively "more stable" overlooks the intricate interplay of anatomical features and biomechanical factors. The hip demonstrates greater inherent, passive stability, while the knee's stability relies more on the intricate coordination of active muscular control and ligamentous support. The relative stability of each joint is context-dependent, varying with individual factors such as age, muscle strength, ligament integrity, and the nature of the imposed forces.

Factors Influencing Joint Stability in Both Hip and Knee

Several factors beyond the inherent anatomy influence the stability of both the hip and knee joints:

-

Age: Ligamentous laxity and muscle weakness associated with aging can compromise the stability of both joints.

-

Muscle Strength: Strong muscles are crucial for active stability in both joints. Weakness can increase the risk of injury and instability.

-

Neuromuscular Control: Proper coordination of muscle activation is vital for dynamic stability. Neurological impairments can disrupt this coordination, increasing the risk of instability.

-

Previous Injuries: Prior injuries to ligaments, cartilage, or bones can significantly compromise joint stability in both the hip and knee.

-

Joint Alignment: Deviations from ideal joint alignment (e.g., genu valgum or varus in the knee, femoral anteversion or retroversion in the hip) can increase stress on the joint structures, leading to increased instability.

-

Obesity: Excess weight places increased stress on both joints, potentially leading to premature wear and tear and increased instability.

-

Activity Level: High-impact activities place greater stress on both joints, increasing the risk of injury and instability.

Conclusion: Understanding the Nuances of Stability

The question of which joint is "more stable" is not a simple one. The hip boasts superior inherent stability due to its deep socket, robust ligamentous support, and powerful muscle encirclement. The knee, while essential for locomotion, exhibits a more precarious balance between its relatively shallow articulation, crucial but less comprehensive ligamentous structures, and reliance on active muscular control.

Understanding the specific anatomical features and biomechanical factors contributing to the stability of each joint is crucial for injury prevention, rehabilitation, and the development of effective treatment strategies. While the hip enjoys a more inherent advantage, both joints require careful maintenance and attention to maintain optimal stability and function throughout life. This understanding highlights the need for a holistic approach to joint health, emphasizing the importance of strength training, proper biomechanics, and injury prevention strategies for both the hip and the knee.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Feet Is 29 In

Mar 19, 2025

-

Does Gold Show Up On A Metal Detector

Mar 19, 2025

-

In Fully Contracted Muscles The Actin Filaments Lie Side By Side

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Many Calories Are In 1g Of Uranium

Mar 19, 2025

-

10 Of 100 Is How Much

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Joint Is More Stable The Hip Or The Knee . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.