Why The Noble Gases Are Unreactive

Kalali

Mar 11, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Why Noble Gases Are Unreactive: A Deep Dive into Atomic Structure and Chemical Behavior

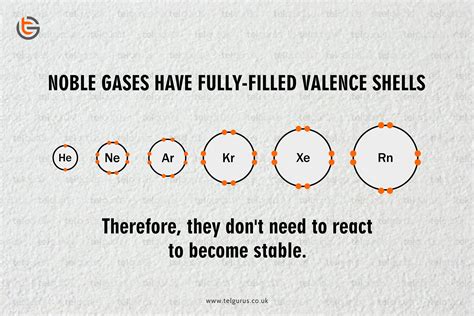

The noble gases, also known as inert gases, are a unique group of elements residing in Group 18 of the periodic table. Their defining characteristic, and the focus of this article, is their remarkable unreactivity. This inherent stability is not merely a curious observation; it stems from a deep-seated arrangement of electrons within their atoms, governed by fundamental principles of quantum mechanics and atomic structure. Understanding why noble gases are unreactive requires a journey into the heart of the atom, exploring concepts like electron shells, valence electrons, and octet rule.

The Significance of Electron Configuration

At the core of a noble gas's unreactivity lies its electron configuration. Each noble gas atom, excluding helium, possesses a full outer electron shell – a characteristic often summarized by the octet rule. This rule states that atoms tend to gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve a stable configuration with eight electrons in their outermost shell. This stable arrangement minimizes the atom's potential energy, making it exceptionally resistant to chemical interactions.

Helium: A Special Case

Helium, the lightest noble gas, presents a slight deviation. Its outermost electron shell, the 1s orbital, can only hold a maximum of two electrons. While not adhering to the octet rule, helium achieves a stable configuration with its filled 1s orbital. This fulfilled valence shell similarly renders helium exceptionally unreactive.

The Octet Rule and Chemical Bonding

Chemical bonding occurs when atoms interact to achieve a more stable electron configuration. Elements readily participate in bonding to gain, lose, or share electrons, achieving the electronic structure of a noble gas. This is because a filled valence shell represents the lowest energy state for an atom, providing maximum stability. Noble gases, already possessing this stable configuration, have little incentive to participate in such interactions.

Types of Chemical Bonds and Noble Gases

The most common types of chemical bonds – ionic, covalent, and metallic – all involve the rearrangement of electrons to achieve a more stable configuration.

-

Ionic Bonds: These bonds form between a metal and a non-metal, with one atom donating electrons to another to achieve a stable octet. Noble gases, already possessing a full octet, cannot easily participate in ionic bonding as they have no tendency to gain or lose electrons.

-

Covalent Bonds: Covalent bonds occur when two non-metal atoms share electrons to achieve a stable octet. While noble gases do not typically form covalent bonds, exceptions exist under extreme conditions. These rare exceptions involve highly reactive species or forcing the atoms into high-energy states.

-

Metallic Bonds: These bonds occur in metals, where electrons are delocalized across a lattice of positively charged metal ions. Noble gases, with their complete electron shells, do not participate in metallic bonding.

Energetics of Noble Gas Reactions

The stability of noble gases is not just qualitative; it has a strong quantitative basis. The ionization energy – the energy required to remove an electron from an atom – is exceptionally high for noble gases. This high ionization energy reflects the strong attraction between the positively charged nucleus and the tightly held electrons in the filled valence shell. Similarly, the electron affinity – the energy change associated with adding an electron to an atom – is very low for noble gases. This low affinity indicates that the atom resists gaining an additional electron, preferring its stable, complete shell.

The Role of van der Waals Forces

While noble gases rarely form chemical bonds, they are not entirely without interatomic forces. Weak van der Waals forces, stemming from temporary fluctuations in electron distribution, can cause noble gas atoms to attract each other weakly. These forces are responsible for the liquefaction and solidification of noble gases at low temperatures. However, these forces are significantly weaker than the strong electrostatic interactions in ionic or covalent bonds, underscoring the inherent unreactivity of noble gases.

Exceptions to the Rule: Compounds of Xenon and Other Noble Gases

For decades, the noble gases were considered entirely inert, with no known compounds. However, this perception was challenged in the mid-20th century with the synthesis of xenon compounds. Under specific conditions, highly reactive species can react with xenon, leading to the formation of stable compounds like xenon hexafluoroplatinate(V), Xe[PtF₆].

Factors Contributing to Xenon Compound Formation

The formation of xenon compounds is a testament to the subtle nuances of chemical reactivity. Several factors contribute to this exception:

-

Large Atomic Size: Xenon is the largest and heaviest of the noble gases. Its large atomic size means that its outer electrons are less tightly held by the nucleus, making them slightly more susceptible to interaction with highly reactive species.

-

High Fluorine Reactivity: Fluorine is the most electronegative element, possessing a strong tendency to attract electrons. This high electronegativity enables fluorine to oxidize xenon and form stable compounds.

-

Specific Reaction Conditions: The formation of xenon compounds generally requires extreme conditions, such as high pressures and temperatures, or the use of highly reactive fluorinating agents.

Other noble gases, such as krypton and radon, have also been shown to form compounds, but these are even rarer than xenon compounds. The formation of these compounds is generally limited to highly specialized research environments.

Applications of Noble Gases

Despite their unreactivity, noble gases find extensive applications across various industries. Their inertness makes them ideal for applications where preventing unwanted chemical reactions is crucial:

-

Lighting: Argon, neon, krypton, and xenon are commonly used in lighting applications, such as neon signs and fluorescent lamps, due to their ability to emit light when an electric current is passed through them.

-

Welding: Argon is commonly used as a shielding gas in welding processes, preventing oxidation and contamination of the weld.

-

Medicine: Helium is used in MRI scanners and as a component of breathing mixtures for deep-sea divers. Radon, despite its radioactivity, has limited application in radiation therapy.

-

Other Applications: Noble gases find use in various other specialized applications, such as in cryogenics, laser technology, and high-performance electronics.

Conclusion: The Enduring Enigma of Noble Gas Unreactivity

The unreactivity of noble gases is a testament to the power of electron configuration in determining chemical behavior. Their filled valence shells represent a state of maximum stability, resisting the tendency to participate in chemical reactions. While exceptions exist, such as the formation of xenon compounds under specific conditions, the overall inertness of these elements remains a cornerstone of their unique properties and extensive practical applications. The continued study of noble gas chemistry continues to unravel the fascinating interplay between atomic structure and chemical reactivity, revealing subtle nuances within what was once considered a wholly inert group of elements. The seemingly simple answer, a filled valence shell, underpins a rich and complex understanding of the fundamental principles governing chemical behavior.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is 6 4 As A Percent

Mar 11, 2025

-

6 Out Of 20 As A Percentage

Mar 11, 2025

-

How Many Inches In 32 Feet

Mar 11, 2025

-

What Is The Percent Of 1 12

Mar 11, 2025

-

How Many Valence Electrons Are In Calcium

Mar 11, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Why The Noble Gases Are Unreactive . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.