The Movement Of An Object Around Another Object

Kalali

Mar 18, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

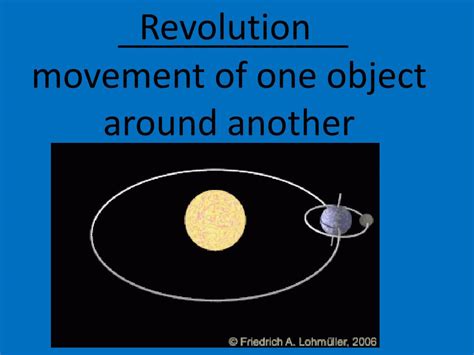

The Movement of an Object Around Another Object: A Deep Dive into Orbital Mechanics

The movement of an object around another object, a phenomenon we commonly associate with planets orbiting stars or moons orbiting planets, is a fundamental concept in physics and astronomy. This seemingly simple observation is governed by a complex interplay of forces and principles, making it a rich area of study with far-reaching implications. This article delves into the intricacies of orbital mechanics, exploring the underlying physics, different types of orbits, factors influencing orbital stability, and the practical applications of this knowledge.

Understanding the Forces at Play: Gravity and Inertia

At the heart of orbital motion lies gravity, the fundamental force of attraction between any two objects with mass. The strength of this force is directly proportional to the product of the masses of the two objects and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers. This inverse square relationship, described by Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation, means that gravity weakens rapidly with increasing distance.

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation: F = G * (m1 * m2) / r^2

Where:

- F represents the force of gravity

- G is the gravitational constant

- m1 and m2 are the masses of the two objects

- r is the distance between their centers

The second crucial element is inertia, the tendency of an object to resist changes in its state of motion. An object in motion will continue in motion with the same velocity unless acted upon by an external force. This inertia is what prevents the orbiting object from simply falling directly into the central object.

The interplay between gravity and inertia is what creates a stable orbit. Gravity constantly pulls the orbiting object towards the central object, while inertia keeps it moving forward. The result is a continuous "falling" around the central object, rather than a direct collision.

Types of Orbits: A Spectrum of Shapes and Sizes

Orbits are not all created equal. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes, each characterized by specific properties:

1. Circular Orbits: The Simplest Case

A circular orbit is the simplest type of orbit, where the orbiting object maintains a constant distance from the central object. In a purely circular orbit, the speed of the orbiting object is constant, and its velocity vector is always perpendicular to the gravitational force. While theoretically possible, perfectly circular orbits are rare in nature.

2. Elliptical Orbits: The Most Common Scenario

Elliptical orbits are far more common in the universe. An ellipse is a closed curve where the sum of the distances from any point on the curve to two fixed points (the foci) remains constant. In an elliptical orbit, one focus is occupied by the central object. The orbiting object's speed varies throughout its orbit, being fastest at its closest point (perihelion for orbits around the Sun, perigee for orbits around the Earth) and slowest at its farthest point (aphelion/apogee).

3. Parabolic and Hyperbolic Orbits: Escape Velocities

Parabolic and hyperbolic orbits represent unbound trajectories. These are open curves, meaning the orbiting object will not complete a closed loop around the central object. An object in a parabolic orbit has exactly the escape velocity, meaning it has just enough energy to escape the gravitational pull of the central object without gaining any additional speed. A hyperbolic orbit indicates the object possesses more than the escape velocity and will move away from the central object indefinitely.

Factors Influencing Orbital Stability: A Delicate Balance

Several factors can affect the stability of an orbit:

1. Gravitational Perturbations: The Influence of Other Objects

The gravitational pull of other celestial bodies can cause perturbations in an orbit, subtly altering its shape and orientation over time. This is especially significant in systems with multiple planets or moons. For instance, the gravitational interaction between Jupiter and the other planets in our solar system significantly affects their orbits.

2. Atmospheric Drag: A Friction-Based Force

For objects orbiting within an atmosphere (like satellites orbiting Earth), atmospheric drag plays a significant role. The friction between the object and the atmosphere gradually slows it down, causing its orbit to decay and eventually spiral towards the central object.

3. Solar Radiation Pressure: A Subtle Force on Satellites

Solar radiation pressure exerts a small but measurable force on objects in space, particularly those with large surface areas and low mass. This pressure can gradually alter the orbit of satellites, requiring occasional adjustments to maintain their desired position.

4. Non-spherical Gravitational Fields: Imperfect Spheres

Planets and stars are not perfect spheres; they have slight bulges and irregularities. These imperfections create non-spherical gravitational fields, which can cause orbital precession – a gradual change in the orientation of the orbit over time.

Kepler's Laws: Mathematical Description of Orbital Motion

Johannes Kepler's three laws of planetary motion provide a precise mathematical description of orbital motion within a two-body system (ignoring the influence of other celestial bodies):

Kepler's First Law (Law of Ellipses): The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

Kepler's Second Law (Law of Equal Areas): A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This law implies that a planet moves faster when it's closer to the Sun and slower when it's farther away.

Kepler's Third Law (Law of Harmonies): The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. This law relates the time it takes a planet to complete one orbit to the size of its orbit.

Applications of Orbital Mechanics: From Satellites to Space Exploration

The understanding of orbital mechanics is crucial for a wide range of applications:

1. Satellite Technology: Enabling Global Communication and Observation

Precise orbital calculations are essential for placing and maintaining satellites in their designated orbits. These satellites provide essential services, including communication, navigation (GPS), weather forecasting, Earth observation, and scientific research.

2. Space Exploration: Reaching Other Celestial Bodies

Successfully navigating spacecraft to other planets, moons, or asteroids requires a deep understanding of orbital mechanics. Complex maneuvers, like gravitational assists (using the gravity of a planet to alter a spacecraft's trajectory), rely on precise calculations to achieve efficient and fuel-saving missions.

3. Understanding Planetary Systems: Unveiling the Mysteries of the Cosmos

Orbital mechanics provides crucial insights into the formation and evolution of planetary systems. By analyzing the orbits of planets and other celestial bodies, scientists can infer information about their history, composition, and interactions.

Conclusion: A Dynamic and Ever-Evolving Field

The movement of an object around another object is a fundamental aspect of the universe, governed by a complex interplay of gravity and inertia. Understanding the principles of orbital mechanics is crucial for a wide range of applications, from the practical deployment of satellites to the ambitious exploration of our solar system and beyond. While the basic principles have been established for centuries, the field continues to evolve, with ongoing research refining our understanding of orbital dynamics and expanding our capabilities to explore and utilize the vast expanse of space. The study of orbital mechanics is not just an exercise in theoretical physics; it's a key to unlocking the secrets of the universe and harnessing its resources for the benefit of humanity. As our technological capabilities advance, our understanding of orbital mechanics will continue to deepen, opening new avenues for exploration and innovation in the cosmos.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Do You Separate Sugar From Water

Mar 19, 2025

-

118 In Is How Many Feet

Mar 19, 2025

-

1 Meter 55 Cm To Feet

Mar 19, 2025

-

12 Oz Is Equal To How Many Ml

Mar 19, 2025

-

How To Find The Change In Enthalpy

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Movement Of An Object Around Another Object . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.